Alumna Feature: “Making an Exonoree” by Anna Marguleus

May 17, 2022

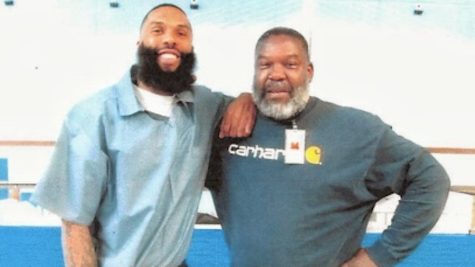

Georgetown University’s Making an Exoneree class has secured 3 exonerations in its 5 years of existence. My group, “Team Faarooq” – made up of Ty Greenberg, Symone Harmon, and myself – believe our case will be the 4th. We are working to exonerate Andrew D. Lee (now Faarooq Mu’min Mansour) who has been in prison for 20 years for a crime he did not commit. With new exculpatory evidence coming to light, it is time we answer the question that has been in Faarooq’s head for the past two decades: what went wrong?

A typical Friday evening transitioned into one that 20-year-old Faarooq Mu’min Mansour would never forget. On March 29th 2002, three dozen police officers and SWAT agents surrounded him outside of his family home in Columbus, Ohio. Without knowing the victim nor the incidents mentioned in the warrant, Faarooq believed this was a case of mistaken identity. Following the advice of his father, he allowed himself to be willingly handcuffed and taken in for questioning. Unbeknownst to him and his parents, Harold and Cynthia, he would never return home.

Faarooq was wrongfully convicted in 2003 of robbery, kidnapping, rape, and murder, and was consequently sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Addressing the jury in his closing speech, Faarooq noted that innocent black men are too often accused of raping and murdering white women. For the past 20 years, he has been one of those innocent black men, wrongfully convicted and wrongfully incarcerated.

At the root of his wrongful conviction is the insidious, pervasive, and fatal grip that racism holds over the United States and its justice system. The Innocence Project found that “innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people.” The statistic is even more stark when the victim is white. Further, it takes approximately 45% longer to exonerate innocent Black people than innocent white people.

Faarooq understood the role that racism played in his trial and conviction. Speaking to his jurors, he said that “white people don’t know how often a black male who is dark-skinned can be mistaken for somebody who is of a lighter complexion.” His jury, supposedly composed of 12 of his “peers,” had only one black member.

Ever since his conviction, Faarooq has maintained his innocence and pleaded for more DNA testing to be done, knowing that it will prove without a doubt that he is telling the truth. His case, however, is at a standstill due to the denial of his motion to request a new trial.

The state used three pieces of evidence to convict Faarooq: a fingerprint, eyewitness identification, and a bracelet.

Faarooq’s fingerprint was one of 111 lifts taken from the front door of the video store. An affidavit from an employee of the store responsible for cleaning the door confirms that it was only occasionally

cleaned, meaning that the prints could have originated from weeks before the date of the crime. Faarooq was in the video store a week prior to the crime to trade in a Playstation 2 for an XBox. No other evidence of Faarooq’s DNA was found.

The three eyewitnesses who saw the suspect inside of the video store on March 25th were all white and their descriptions of the suspect’s physical appearance did not match Faarooq. Two of them picked Faarooq out of a photo lineup. The photo of Faarooq used in the lineup, however, was around a year old and did not match his appearance at the time of the crime. Further, the defense never called an expert witness to address potential issues with the administration of the photo lineup, in addition to concerns of cross-racial identification, stress factors, and weapon focus.

A bracelet, identified as possibly belonging to the victim, was found near Faarooq’s jacket on the day of the crime. The victim’s family, however, could not say conclusively that the bracelet was hers, and neither the victim’s nor Faarooq’s DNA was found on it. The victim’s co-worker did not recall her wearing a bracelet, and the victim’s father said that she could not wear a bracelet because of a scar on her wrist. Additionally, an individual who lived in the house where the bracelet was found admitted to being a lookout for a robbery in which the bracelet was stolen, and in which Faarooq had no involvement.

Having reviewed the case in its entirety and gotten to know Faarooq on a personal level, we support his innocence – and know that significant exculpatory evidence does exist.

The gun stolen during the commission of the crime was found on a career criminal in Atlanta, Georgia months after the murder. A friend of Faarooq’s has signed an affidavit stating that the two of them were together at his house while the crime was committed. And most importantly, DNA profiles of two different men were found on the victim and never run through CODIS (Combined DNA Index System). Faarooq was scientifically excluded as matching either of these profiles. CODIS is a national database made up of the DNA profiles of convicted offenders, profiles developed from evidence in unsolved crimes, and profiles developed for the identification of missing persons. We are hoping to finally have the DNA run through this system.

Now is the time to show Faarooq you believe in his innocence. Join us in our fight to exonerate him by spreading the word and garnering awareness.

To see how you can get involved, visit our campaigning sites here.